Illinois Achieved a Broad Climate Law. How Do Supply and Demand Respond?

In Brief

Illinois passed a major climate-justice law in 2021. How firm of a template is it?

Poring over the details with experts, our reporter learned how the bill does and doesn't stoke demand for and spread access to renewable power.

Go for a ride through the bill's promise and potential enhancements, and think about retooling it for where you live.

This September, on a sunny late summer morning in Chicago, Illinois Governor J. B. Pritzker signed a comprehensive piece of environmental legislation called the Climate and Equitable Jobs Act (CEJA). Standing on the shore of Lake Michigan, just outside the world-famous Shedd Aquarium, Pritzker heralded the bill as a major step forward for a state with strong ancestral ties to the coal mining industry.

The bill sets an ambitious net-zero target, schedules the closure of the state’s largest emitter—the Prairie State coal plant—and provides funding for environmental vocational programs in disadvantaged communities. It has been praised by environmental activists, business leaders, and policymakers. It’s natural to ask: how did the fourth largest coal producer among U.S. states in 2020 enact such a substantial piece of environmental legislation?

Part of the answer is politics. With a Democratic trifecta that took power in 2019, there has been increased momentum towards climate policy. Plus, a bribery scandal involving utility company ComEd and Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan sidelined some of the parties who had historically opposed climate regulation in the state.

It’s not all about politics, of course. Also at play is the state’s desire to capitalize on broader trends in the clean energy industry. Those trends are leading governments around the world to adjust policies. But though they start with plummeting costs for renewables, these trends only open an opportunity to supply a place with fossil-free power. The question of creating demand for that power remains open.

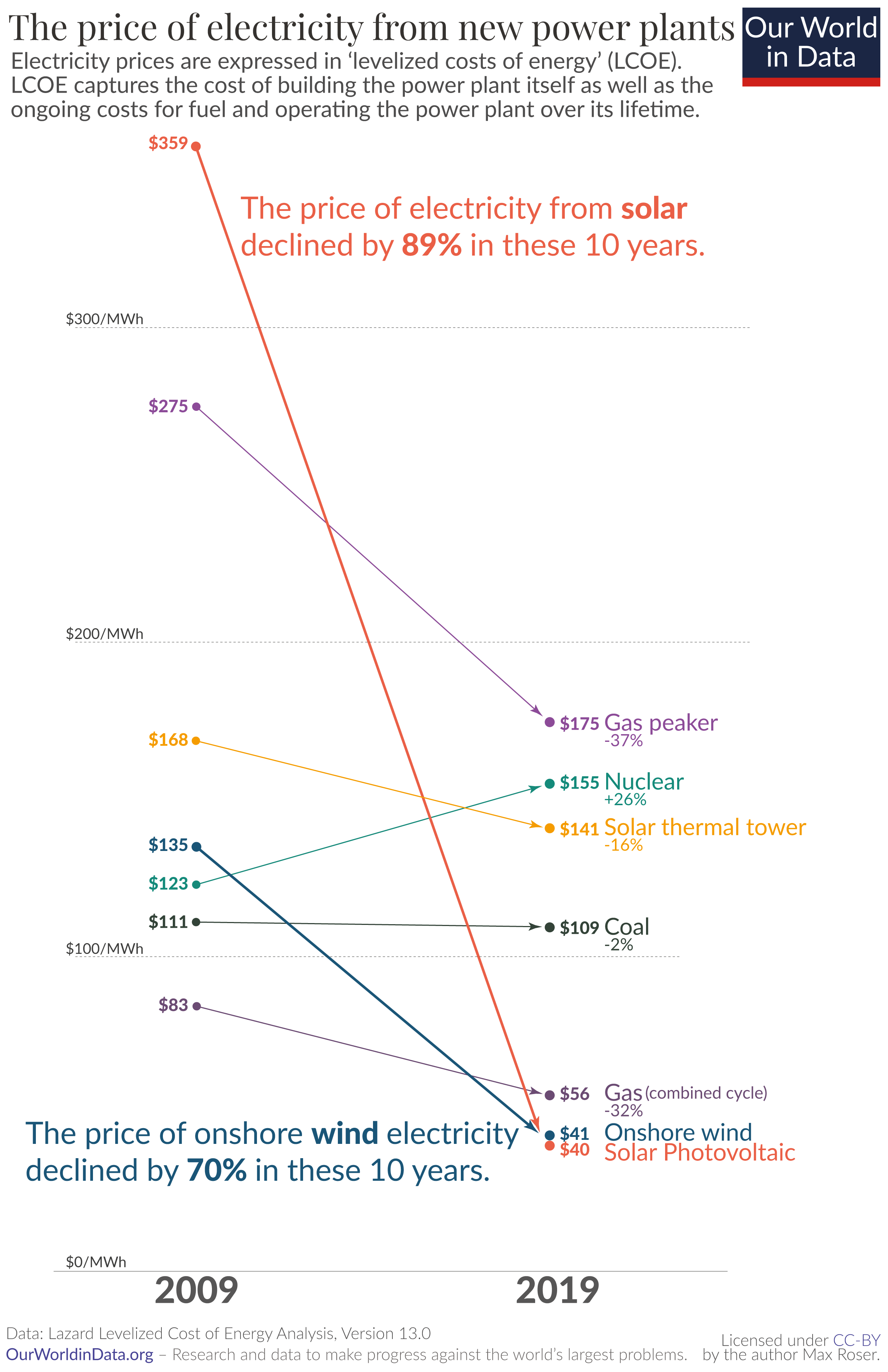

For the past decade, until 2021, U.S. wind and solar prices have declined every year. In June, Bloomberg Green’s Will Mathis reported that “it’s now cheaper to build and operate new large-scale wind or solar plants in nearly half the word than it would be to run an existing coal or gas-fired power plant.” Why, then, is Illinois’ bill so unusual?

One reason is that economics alone don't impel clean-energy adoption, yet. Without significant political momentum, like the Democratic trifecta in Illinois, low prices aren’t sufficient to complete the U.S. clean energy transition. The price of solar photovoltaic has declined by 89% since 2009, and the country has added about 97 gigawatts of solar capacity since then. While these are impressive growth rates, they are building off a very low 2009 base. As a result, just about 3% of US electricity is generated from solar sources today. A lot of financial work remains.

Both solar and wind sources suffer from an intermittency problem. This creates a mismatch between generation and demand, famously known as the California “duck curve.” On bright sunny days, a large solar array can generate so much more power than is demanded by the grid that it drives electricity prices below zero.

On one hand, negative electricity prices open the door to intriguing technological possibilities. Instead of being wasted, excess electricity could be used to power large-scale carbon capture systems that abate emissions from natural gas plants before they reach the atmosphere or to drive electrolysis systems that can extract clean hydrogen atoms from water molecules. Both hydrogen fuel cells and large-scale carbon capture systems seem poised to play an important role in building a decarbonized energy grid but require a lot of power to run. Ensuring that this power runs clean would be a significant step forward.

On the other hand, current solar and wind prices can pose problems for developers. Intermittency means that that peak renewable output may not occur when demand is high. In addition, renewables often have a low levelized cost of energy (LCOE) and low capture prices. (That's what market-makers call the prices at which a generator sells electricity.) Research from BDO Global, covering 2011 – 2015, suggests that these factors driven have contributed to renewable assets seeing prices below those predicted by developer’s cash flow models. This may reduce the market’s expectation for future renewable projects, especially those without government aid.

These features suggest that the clean energy transition cannot be solved solely by market design, competition, or other economic forces. What might solve that problem?

Jay Readey, an Illinois-based community developer, suggests that a key solution is government policy that increases demand for clean power while ensuring economic gains for underserved communities. Our question now becomes: does CEJA accomplish that goal? If not, what additional policy measures will be needed? To find an answer, I surveyed Illinois-based energy consultants, community organizers, and social entrepreneurs.

Before diving in, let’s highlight the main pieces of the legislation. It:

- Mandates that Illinois reach 100% clean energy by 2050 and 100% carbon free electricity by 2045.

- Dictates that the Prairie State coal plant cut emissions to zero by 2045, which likely will necessitate its closure.

- Commits $580MM (double the current investment) annually towards wind and solar projects to generate 50% of energy from those sources by 2040.

- Delivers $700MM over five years to support nuclear power plants in the state.

- Provides up to $80MM in annual funding for electric vehicle infrastructure, with about half of the funds directed towards disadvantaged communities.

- Creates diversity and equity requirements for renewable energy projects and provides support for disadvantaged contractors, setting aside over $80MM for development programs in equity-focused communities.

- Forms a statewide green bank that will allocate seed capital to underrepresented businesses and finance clean energy projects.

- Changes the ratemaking system to better line up utility company incentives with clean energy goals.

- Creates a $40MM program to assist communities that rely on fossil fuel jobs transition to the clean energy economy and creates incentives to build renewable infrastructure in those places.

- Provides financing to retain jobs in nuclear power plants.

CEJA’s topline net-zero goals make Illinois only the sixth state in the country to set such a benchmark. They signal to renewable developers that the state is open for business and that utility-scale renewable demand will be substantial.

This would shift Illinois' economic ground. As of July 2021, only 6% of the state’s electricity was provided from renewable sources, compared to nearly 20% nationwide. Recognizing the need to close that gap, the state apportioned almost $600MM per year, double the current total, to renewable energy subsidies. Industry experts and policymakers agree that setting aggressive goals and backing them up with serious funding is a necessary first step reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

Energy professionals were also pleased that CEJA included financial and employment support for the state’s nuclear power plants. At over 51%, Illinois generates more power from nuclear plants than any other state in the country, and will likely not be able to meet those ambitious net-zero goals if its nuclear facilities are shut down.

Although it’s controversial among environmentalists, energy professionals agree that nuclear is clean in carbon terms and its low levelized cost of energy makes existing power plants cheap and efficient ways of generating carbon-free power. There is some concern that the $700MM directed towards the Byron, Dresden, and Braidwood nuclear plants is insufficient since it is below the $5 billion requested by Exelon, but the figure is supported by an independent assessment.

In addition, the bill has won considerable praise from community development organizations around the state. Malik Benjamin, Business Development Manager at Elevate, a Chicago-based organization whose mission is to ensure equitable access to clean energy and water, was glad that the bill directs clean energy dollars to underserved neighborhoods and communities historically reliant on the fossil fuel industry. This is important because a successful clean energy transition requires delivering positive economic benefits to the public at large. That obliges policymakers to reduce the impact between the “winners” and “losers” of the transition.

Current clean energy investments disproportionately support white-owned businesses, but Elevate hopes that the $80MM allocated for clean energy workforce and contractor development programs around the state will reduce that imbalance. In addition, the bill includes five times the funding for Illinois’s Solar for All program, a community solar initiative administered by Elevate that targets disadvantaged communities. This effort seems likely to spur distributed generation (DER) infrastructure in underserved neighborhoods of Chicago, a noble goal that can help deliver clean power to places it doesn’t currently flow.

Despite the praise CEJA has received, several Illinois energy experts had thoughts on how the legislation could be improved. Jason Feldman is CEO of Green Era Chicago, a community development partnership that brings clean energy initiatives to the city’s Southside. He wished that the bill established a low carbon fuel standard (LCFS). These standards set requirements for the carbon intensity (emissions per unit of energy) of transportation fuels to encourage the use of cleaner energy like renewable biogas. Market participants can decide the mix of fuels used to meet the standard. Fuels with a carbon intensity below the standard generate credits that can be sold. LCFS can help make heavy industry and combustion-based processes more efficient and would effectively complement the electricity focus of CEJA.

Transmission, a vexing problem of utility-scale renewable deployment, is also an area for improvement. While the bill calls for a plan to increase renewable electricity transmission throughout the space, it does not comment on the content of the plan, necessary funding, or specific goals. Because renewable generation tends to occur far away from population centers, there is a large infrastructure challenge with delivering that power from its source to users. This challenge is amplified by regulatory concerns. It can take over a year to connect a utility-scale project to the grid via PJM, one of the state's two regional transmission organizations. Streamlining regulation and providing additional staff at the RTO level would help CEJA make Illinois more attractive for large-scale renewable development.

One way to handle the transmission issue is to invest in distributed energy resource (DER) systems. Christian Sanchez, a senior energy consultant at Sargent & Lundy, suggested that a Virtual Power Plant (VPP) clause would enhance CEJA. VPVPs create cloud-based networks of DER units to better monitor, schedule, and trade their output. By aggregating capacity across many units, VPPs can simulate the balancing ability of larger power plants and produce reliable power. This helps alleviate the intermittency problem by scaling up generation and utilization. The VPP would work through a public non-profit, which would help keep rates low for participants. Essentially, it would create a virtual public utility.

Sanchez’s idea resonates with the green bank provisions of CEJA. The green bank will support DER infrastructure in low-income communities. Small solar projects like these comprise a significant portion of the Illinois solar landscape. The VPP will allow these small DER projects to work together as both power producers and consumers. Entry costs to wholesale markets would decline, and underserved communities would have greater representation in the Illinois energy system.

Despite potential enhancements, CEJA represents a significant leap forward in the state’s climate ambitions and is poised to serve as a model for the rest of the Midwest. Perfect is the enemy of the good, especially in climate policy, where progress has been far too slow for far too long. While Illinois has work to do, fully implementing provisions in CEJA would yield a significant victory for climate and clean energy policy.